Hiyokebashi Bridge in the Naiku of Ise Jingu. Bridges symbolically connect this side and the far side, and the Japan’s creation myth notably begins with the Ame-no-ukihashi, or Floating Bridge of Heaven.

The origins of Ise Jingu date back 2,000 years. Affectionately called “O-Ise-san,” the official name of Ise Jingu is simply “Jingu.” It is comprised of the Kotaijingu (Naiku), which enshrines Amaterasu Omikami, the sun goddess and ancestral deity of the Japanese people; and Toyoukedaijingu (Geku), dedicated to Toyouke no Omikami, the deity responsible for Amaterasu Omikami’s meals and guardian of various industries such as food, clothing, and shelter. In addition to these, there are 125 other shrines in the area, including lower rank (betsugu), auxiliary (sessha), and subordinate (massha) shrines. It is considered the principal shrine among the approximately 80,000 shrines across the whole of Japan and a sacred national area.

Ise Jingu’s biggest festival is the Shikinen Sengu, held once every 20 years. During this event, all shrine buildings are reconstructed, and the deity of Ise Jingu is transferred to a new shrine in a tradition of over 1,300 years. This symbolic ritual renews the deity’s residence and furnishings and is believed to preserve the sanctity of the site.

A Sacred Journey to O-Ise-san: The Spiritual Home Everyone in Japan Dreams of Visiting Once in a Lifetime

The limpid Isuzugawa River, an area for purification (mitarashi).

The Ujibashi Bridge, traversing the Isuzugawa River, serves as the entrance to the Naiku, a gateway from the everyday world to the sacred realm. The pilgrimage begins with a bow in front of the Ujibashi Bridge. Every 20 years, the inner torii gate is reused to rebuild the Seki no Oiwake torii at the foot of Suzuka Pass, and the outer torii becomes that of Kuwana’s Shichiri no Watashi, thereby completing their two-decade cycle.

The Kaguraden (sacred stage), where amulets and charms can be received.The shogu (main shrine) in the Naiku, where Amaterasu Omikami is enshrined.

The Geku

The Higoto Asayu Omikesai ritual has been performed twice daily without fail for about 1,500 years, where food offerings are made to Amaterasu Omikami in the morning and evening.During the Edo period (1603–1860), the pilgrimage to Ise became widespread among commoners, with approximately five million people visiting annually at its peak. One way, it took 15 days from Edo (Tokyo), 5 days from Osaka, and 3 days from Nagoya, with pilgrims walking from regions as far as Tohoku and Kyushu. The development of transportation networks, including the Gokaido (Five Routes), and the availability of inns and entertainment facilities en route made the journey both accessible and enjoyable for many pilgrims. After visiting Ise, travelers would often continue on to Kyoto or Osaka for sightseeing.

For those unable to travel due to illness or old age, there were even dogs that made the pilgrimage on behalf their owners. To make clear that the dog was a proxy pilgrim, the owner would attach travel expenses and a note explaining the purpose of the journey—okage mairi, meaning a pilgrimage to Ise—to the dog’s collar using a shimenawa (sacred rope). The people of the Edo period, driven by their strong faith, would provide food and shelter for these dogs, believing that by assisting them they would accumulate merit of their own. Indeed, it could well be that just such warm-heartedness and generosity at the time gave rise to the phenomenon itself.

Today, at Okage Yokocho, so-called okage inu, or okage dog, merchandise inspired by stories from that era can be found for sale.

Okage inu can be seen in Utagawa Hiroshige’s famous ukiyo-e woodblock print Crossing Miyagawa River to Visit Ise Shrine. In the Edo period, regardless of status, anyone carrying a talisman from Ise was permitted to wander from their home without prior permission. Food and lodging was sometimes sponsored by feudal lords and wealthy individuals, making the pilgrimage less burdensome and more enjoyable. Travelers could also purchase local specialties from Kyoto and Osaka, making the pilgrimage a journey everyone dreamed of taking at least once in their lifetime. The phrase “ Issho ni ichi-do wa O-Ise mairi ” (“At least once in a lifetime, make a pilgrimage to Ise Jingu”) remains to this day, highlighting Ise Jingu’s place in the hearts of the Japanese people.

The path that continues from Ise Jingu to the Kumano Sanzan, or Three Grand Shrines of Kumano—Kumano Hongu Taisha, Kumano Nachi Taisha, and Kumano Hayatama Taisha—is known as the Kumano Kodo Iseji, and is considered a prayer path for travelers visiting the Kumano Sanzan after paying homage to Ise Jingu. The saying “Ise e nana-tabi, Kumano e san–do” (“Seven times to Ise, three times to Kumano”) reflects the importance of both Ise Jingu and the Kumano Sanzan for people to visit. The Kumano Kodo Iseji retains its historic character to this day and is designated as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site.

Ise Jingu

Address: Kotaijingu (Naiku) 1 Uji Yamada-cho, Ise-shi, Mie-ken

Toyouke Daijingu (Geku) 279 Toyokawa-cho, Ise-shi, Mie-ken

Tel.: 0596-24-1111 (9:00–16:00)

Hours: 5:00-18:00 (January–April, September)

5:00–19:00 (May–August)

5:00–17:00 (October–December)

Oharai-machi Street, Preserving the Atmosphere of the Sangu Kaido

The Sangu Kaido direct path leading out from Ise Jingu, is also known as Oharai-machi Street. During the Edo period, this route, stretching about 800 meters from Ujibashi Bridge along the Isuzugawa River, was lined with buildings where lower-ranking priests and commoners would be purified and lodgings were provided. Even today, walking down this historic street brings you back to the rich atmosphere of that former era.

Akafuku Mochi: The Standout from a Mochi Culture Born of the Ise Pilgrimage

Traveling from all over Japan to Ise, pilgrims often turned to mochi rice cakes, which were both filling, quick, and easy to eat, for sustenance—to such an extent, in fact, that the Sangu Kaido from Kuwana to Ise was also known as the Mochi Road, with many famous mochi treats offered along the way to welcome travelers.

Akafuku, located in the center of the Sangu Kaido, was established in 1707. Its main product, Akafuku mochi, is modeled after the rippling Isuzugawa River flowing through Ise Jingu’s sacred precincts. Three lines of in the an (red bean paste) represent the clear stream, and the white mochi represents the pebbles on the riverbed.

The smooth texture of both the an (red bean paste) and mochi makes Akafuku mochi a popular souvenir from the Tokaido road. The folded box containing 8 pieces (pictured) is priced at 900 yen. (Prices at time of writing.)The summer exclusive Akafuku-gori (800 yen) is an Ise seasonal specialty. It features shaved ice drizzled with refined, sweetened matcha syrup, with specially prepared red bean paste and mochi inside. A trip to Mie is worth it just for this exquisite treat, available at locations besides the main Akafuku store, such as Dangoro Chaya in Okage Yokocho.Akafuku Honten

Address: 26 Uji Nakanokiri-cho, Ise-shi, Mie-ken

Tel.: 0596-22-7000 (general inquiry)

Hours: 5:00–17:00 (hours may vary during peak seasons)

Closed: Open year round

Dangoro Chaya

Address: 52 Okage Yokocho, Uji Nakanokiri-cho, Ise-shi, Mie-ken

Tel.: 0596-23-8808

Hours: 10:00–17:00 (LO 16:30, varies by season)

Closed: Open year round

Try Local Food from Mie Prefecture amid the Festival-like Bustle of Okage Yokocho

Located roughly in the middle of Oharai-machi Street sits Okage Yokocho, an area gathering together the Ise’s diverse delicacies. Its main feature is a recreation of a street from the Edo and Meiji periods (about 150–200 years ago), with over 50 shops, including food and souvenir stores, spread across more than 13,000 square meters.

Situated within Okage Yokocho, Fukusuke is a shop serving Ise udon, a local Mie specialty often enjoyed by locals at home. Ise udon is characterized by its soft, thick noodles and a rich sauce made from dashi borth and Ise tamari (soy sauce). It is said to have been created to soothe the stomachs of travelers after long journeys, and the udon noodles were boiled once and kept ready to serve quickly, akin to an early form of fast food.

Handmade Ise Udon (800 yen), available in limited quantities.

The handmade Ise udon at Fukusuke features a special, slightly sweet and spicy sauce made with tamari and very thick, soft noodles. Usually simply topped with green onions, its rich appearance belies a simple flavor that goes down smoothly, making it a popular local snack.

Fukusuke

Address: 52 Okage Yokocho, Uji Nakanokiri-cho, Ise-shi, Mie-ken

Tel.: 0596-23-8807

Hours: 10:00–17:00 (LO 16:30, varies by season)

Closed: Open year round

Normally, shimenawa (sacred ropes) are displayed only during the New Year period, but in the Ise region, they are hung year-round. The wooden plaque on the front often reads “Somin Shorai Shison Kamon” (“entrance to the home of a descendant of Somin Shorai”), which serves as a talisman to prevent evil spirits from entering the home.

<Ise Honkaido: Okitsu-juku>

Experience the Centuries-Old Scenery and Hospitality of Travelers from Osaka to Ise

The Kawachi family, who once ran a dyeing shop specializing in indigo, has revived the business under the name “Shikisou,” offering experiences in indigo and plant-based dyeing. Shikisou: 1298 Okitsu, Misugi Town, Tsu City, Mie-ken, tel. 080-6946-4804 (Kawachi)The Ise Honkaido is an approximately 170-kilomoter-long road from Osaka’s Tamatsukuri Inari Shrine through Nara to Ise, the shortest route for travelers from the west aiming for Ise. Although steep and riddled with mountain passes, it was revered as the shin’i ni kanau michi, or “path of divine will,” because it overlaps with the route taken by Yamatohime when she guided Amaterasu Omikami to Ise.

Following the Nanbokucho period (1337–1392), the Kitabatake clan, who ruled the area, established their headquarters in Misugi Town, Tsu City, transforming it into a castle town. As visits to Ise spread among commoners, the Ise Honkaido became a major route for many. In the Edo period, the post towns of Ishinahara, Okitsu, and Kamitage within the Misugi Town area provided rest for travelers before and after mountain passes. Misugi Town, which thrived on forestry, continued to prosper until around 1955, and signs of its past, including movie theaters, pachinko parlors, and banks, are still visible.

Nushiya sold daily necessities such as salt and tobacco from the Meiji era (1868–1912) to the Showa era (1926–1989). It was founded by craftsmen from the Yoshino region in Nara Prefecture, known as the birthplace of lacquerware. The signs hanging above the store date back to the Taisho era (1912–1926).Okitsu-juku today has a quaint street known as Noren Street, where local hatago inns, pharmacies, miso shops, fishmongers, and dye shops, and more display hanging noren curtains. The noren bear Edo-period shop names, conjuring up the ancient townscape for visitors. The historical tour of the Ise Honkaido road, hosted by Misugi Resort’s Inaka Tourism initiative, includes a course in which a guide takes visitors to private homes, providing insights into the town’s history, the daily life of its residents, and its enduring spirit of hospitality.

Noren Street in Okitsu-juku. Each house displays a noren with an Edo-period shop name.Guide Kenichi Nakagawa and Sanae Torii, owner of Manekiya, who served tea during the visit. Manekiya, originally a specialist oil shop, used to serve tea to travelers during the Edo period.From Okitsu-juku, it is about a 3-minute walk from JR Meisho Line’s Ise-Okitsu Station. The untouched nature seen from the train window between Ise-Kamakura Station and Ise-Okitsu Station offers a glimpse of the numerous mountain passes of the Ise Honkaido.Inaka Tourism “Historical tour of the Ise Honkaido road”

Address: 5990 Yachi, Misugi-mura, Tsu-shi, Mie-ken (Hinotani Onsen Misugi Resort)

TEL: 059-272-1155 (reception hours: 9:00–17:00)

<Seki-juku> The Post Town Where Kansai and Kanto Cultures, and Edo, Meiji, and Taisho Times, Blend Together

During the Edo period, Seki-juku was said to have 15,000 people travel through every day. Crossing the 4–5-meter-wide street would sometimes take nearly an hour due to congestion. Pictured in the distance is Suzuka Pass, whose appearance travelers at the time used as a barometer to predict the weather.Seki-juku is the site of the Suzuka Seki, one of the Three Great Checkpoints of Old Japan established in the year 701. During the Edo period, it became the 47th post town on the Tokaido route, branching into the Yamato Kaido toward Nara from its western junction and the Ise Betsu Kaido towards Ise from its eastern junction. The town thrived with travelers going to Ise and the daimyo making their periodic visits to Edo (Tokyo). For travelers coming from Kyoto to Ise, Seki-juku was an important post town where they could rest after crossing the difficult Suzuka Pass. As a place on the boundary between Kanto and Kansai, Seki-juku used both the silver currency of the west and the gold currency of the east.

Approximately 1.8 kilometers of Seki-juku, nearly the entire area, has been designated as the only Important Cultural Buildings Preservation District on the Tokaido route. About 210 townhouses built from the Edo period to the Meiji era still stand to this day, offering a captivating glimpse of the scenery seen by travelers of that bygone era.

Edo-period buildings were designed asymmetrically, considered auspicious according to Feng Shui. In the Meiji era, on the other hand, symmetry was considered to be aesthetically pleasing and buildings were designed accordingly.The shop sign above Fukawaya is the only surviving iori kanban (signboard) in Seki-juku. Iori kanban were devised by Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first shogun of the Tokugawa shogunate, established in 1603, to help travelers on the Tokaido avoid getting lost. One side of the signboard had kanji, and the other side had hiragana, allowing travelers to head towards Edo by reading the kanji or towards Kyoto by reading the hiragana.Seki-juku boasts numerous attractions, such as the Seki Machinami Museum, which showcases Edo-period townhouses and Seki Jizo-in, home to Japan’s oldest statue of Jizo Bosatsu, guardian of children and travelers. Amongst them is Fukawaya, a historic confectionery shop established about 380 years ago by the Hattori family, known to be descendants of ninjas.

Since being created by Hattori Iyoyasushige, a descendant of the ninjas, during the Edo period, the seki-no-to rice cake has been made according to a recipe passed down through oral tradition. It was considered a luxury confection unaffordable to ordinary people at the time.Back then, Fukawaya delivered seki-no-to, a sweet made by wrapping red bean paste in soft mochi rice cake and dusting it with Tokushima Prefecture’s wasanbon sugar, to the residences of daimyo who stayed in Kyoto’s Omuro Gosho (Ninna-ji Temple) and Seki-juku. However, the confectionery shop was actually a cover for the Hattori family’s covert intelligence activities. According to the 14th-generation head of the family, Hattori Kichiemon Aki, “At that time, espionage involved getting into people’s good graces. The goal was to gather information to smooth human relationships and pass it on to the Tokugawa shogunate.” Perhaps surprisingly, the history of this small sweet involves a supporting role in upholding the Tokugawa shogunate from behind the scenes.

14th-generation Hattori Kichiemon Aki is also a guide for the Seki-juku Volunteer Guide Association, regaling visitors with tales of ninjas and the history of Seki-juku.Fukawaya

Address: 387 Naka-machi, Seki-cho, Kameyama-shi, Mie-ken

Tel.: 0595-96-0008

Hours: 9:30–18:00 (until sold out)

Closed: Thursdays (open on public holidays)

Seki-juku Volunteer Guide Association (Seki-juku Hatago Tamaya Historical Museum)

Address: 444-1 Naka-machi, Seki-cho, Kameyama-shi, Mie-ken

Tel.: 0595-96-0468

Reception Hours: 9:00–17:00

Closed: Mondays

※Group tours available for 10 or more persons; English assistance available; reservations 3 months to 1 week in advance

<Shichiri-no-Watashi (Seven-Ri Crossing) Remains>

Shichiri-no-Watashi: Entering Ise Province from Edo via the only sea route on the Tokaido

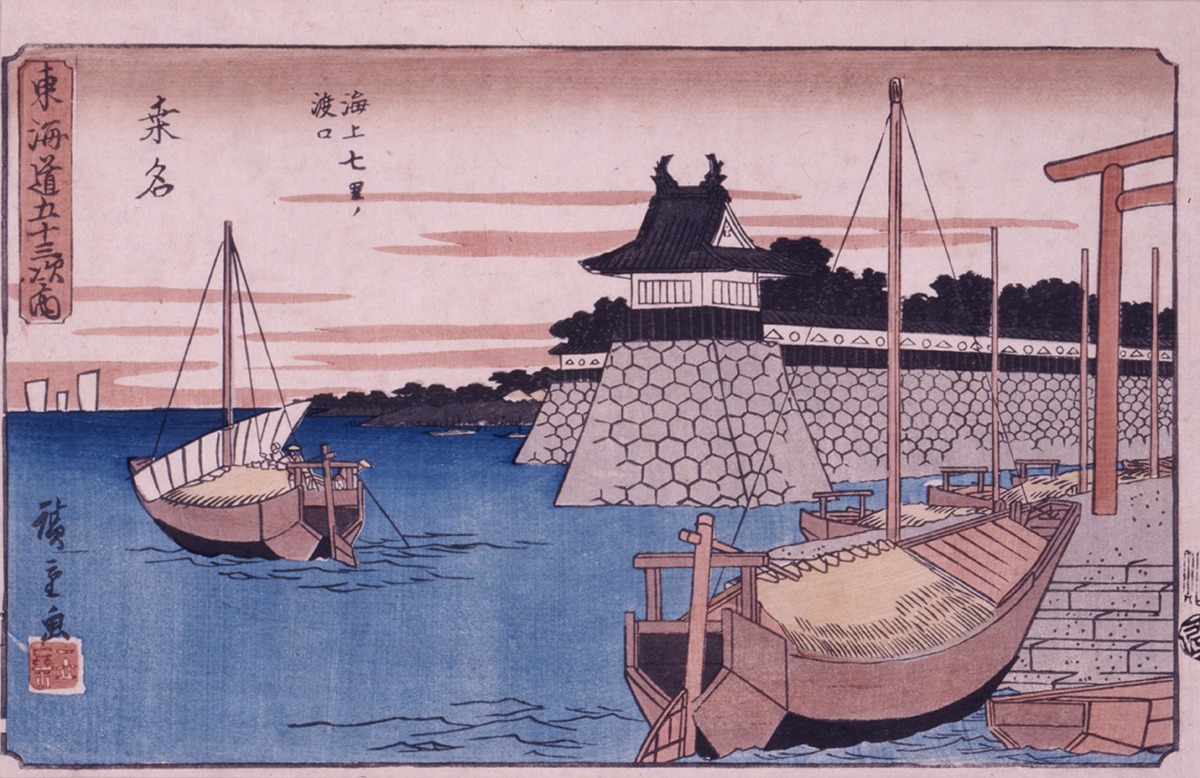

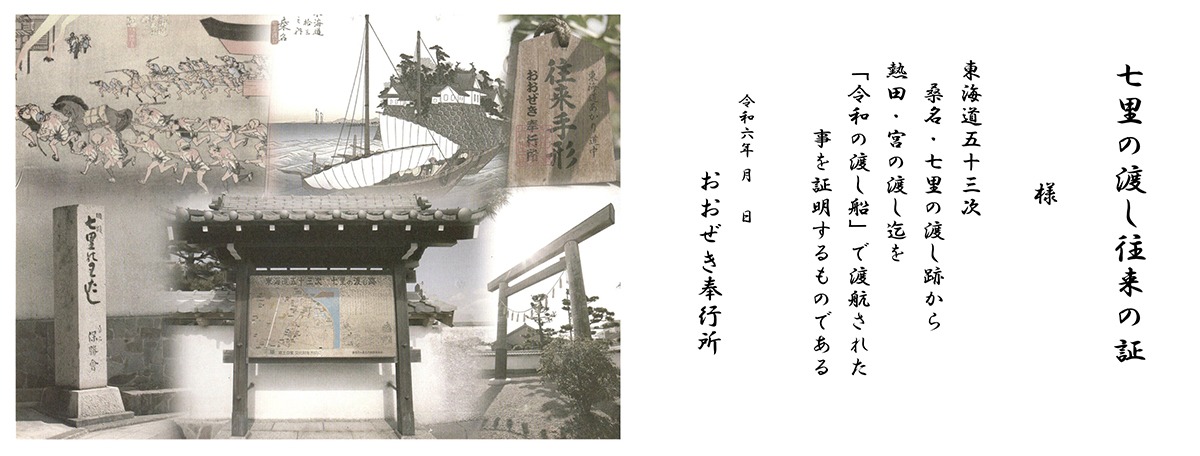

The first torii gate of Ise Province at Shichiri-no-Watashi Remains. The first torii, built during the Tenmei era (1781–1789), was erected by merchants from Kuwana who gathered donations from the Kanto region.Travelers from Edo would head for Ise through the Tokaido route connecting Edo and Kyoto. The Shichiri-no-Watashi was the only sea route on the Tokaido, linking the 41st post town of Miya-juku (Atsuta-ku, Nagoya-shi, Aichi-ken) and the 42nd post town of Kuwana (Kuwana-shi, Mie-ken). The term “shichiri” comes from its distance of seven ri (about 28 kilometers).

Kuwana developed as a key transportation hub for both water and land routes connecting the Kiso Sansen, or Kiso Three Rivers—the Kiso, Nagara, and Ibi Rivers—Owari in Aichi Prefecture, and Ise. Endless people and goods passed through the town on their way to Ise, Kyoto, and Edo. During the Edo period, the town boasted over 100 inns, making it the second most significant post town on the Tokaido after Miya-juku. For travelers coming from the east, Kuwana was the gateway to Ise Province. The torii standing at Shichiri-no-Watashi is known as the first torii of Ise Province and was relocated there from the torii at Ujibashi Bridge in Ise Jingu’s Naiku.

Another symbol alongside the torii is the Banryu Yagura, or Banryu (crouching dragon) turret. Kuwana Castle, once a famous castle along the Ibi River, had 51 turrets. Among these, one was designed with tiles shaped like a dragon crouching before ascending to the heavens (banryu), said to monitor ships arriving at Shichiri-no-Watashi. The Banryu Yagura was recreated and built in 2003 as part of the sluice gate’s management building, with its second floor serving as a free observation room and exhibition space.

Utagawa Hiroshige’s Kuwana: Sea Ferry Terminal at Shichiri from the series The Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido (1833–34), held at the Kuwana City Museum (reproduction prohibited).

Above: Utagawa Hiroshige’s Kuwana: Sea Ferry Terminal at Shichiri from the series The Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido (1833–34). Depicted in the center is the Banryu Yagura. Below: The sluice gate management building, built in 2003 to replicate the Banryu Yagura.With the opening of the Kansai Railway’s Kuwana Station in 1895, which was connected to Nagoya the following year, the need for a ferry crossing at Shichiri-no-Watashi disappeared. What’s more, the area around Shichiri-no-Watashi suffered significant damage from the Ise Bay typhoon of 1959, necessitating the construction of levees. However, in spite of its changes over time, Shichiri-no-Watashi remains a notable part of Japan’s history. Today, Oozeki Co., Ltd., operates small charter boats on a route nearly identical to the original.

Passengers taking Oozeki’s Shichiri-no-Watashi route receive a certificate of passage. Oozeki Co., Ltd.: 82-1 Tatsuta-cho, Kuwana-shi, Mie-ken, tel. 0594-22-4867.THE FUNATSUYA, located near Shichiri-no-Watashi, is a restaurant and wedding venue built on the site of Otsuka Honjin, the most prestigious inn in Kuwana-juku where daimyo, court nobles, and shogunate officials stayed during their official travels. The restaurant preserves the original pillars and beams— crafted by ship carpenters rather than temple carpenters—of the former inn. The restaurant (currently offering dining only in private rooms) serves Italian and Japanese cuisine using seasonal ingredients from Mie Prefecture. THE FUNATSUYA: 30 Senbacho, Kuwana-shi, Mie-ken, tel. 0594-22-1880 (restaurant).The Hamaguri Kaiseki course (from 3 persons, starting at 9,900 yen per person) features the specialty grilled large clams, a signature dish inherited from the restaurant’s inn days.Shichiri-no-Watashi Remains

Address: Sannomaru, Kuwana-shi

Banryu Yagura (Sluice Gate Management Building) 2nd Floor Observation Room Hours: 9:30–15:00

Closed: Mondays (on national holidays, closed the following day), December 28–January 4

<Yasunaga Mochi>

A Stick-Shaped Mochi Invented by Kuwana’s Feudal Lord, Delicious Fresh or Grilled

Made using traditional methods without preservatives, Yasunaga mochi has a shelf life of 3 days. It becomes firmer each day, but when roasted over a fire, it develops a different, savory flavor compared to fresh. A pack of 10 mochi for 926 yen. (Prices at time of writing.)Yasunaga mochi, sold at tea houses along the Yasunaga Kaido, were a popular snack for travelers passing through Kuwana-juku. It is said to have been invented by Matsudaira Sadanobu, the grandson of Tokugawa Yoshimune, the eighth shogun of the Tokugawa shogunate, who retired in Kuwana. Founded in the mid-Edo period, Yasunaga Mochi Honpo Kashiwaya makes Yasunaga mochi by hand-roasting thinly rolled mochi rice cakes filled with plenty of sweet bean paste. Supposedly, the elongated shape made it easy for travelers to carry.

Yasunaga Mochi Honpo Kashiwaya

Address: 1-74 Chuo-cho, Kuwana-shi, Mie-ken

Tel.: 0594-22-1197

Hours: 8:00–18:00 (until sold out)

Closed: Open year round

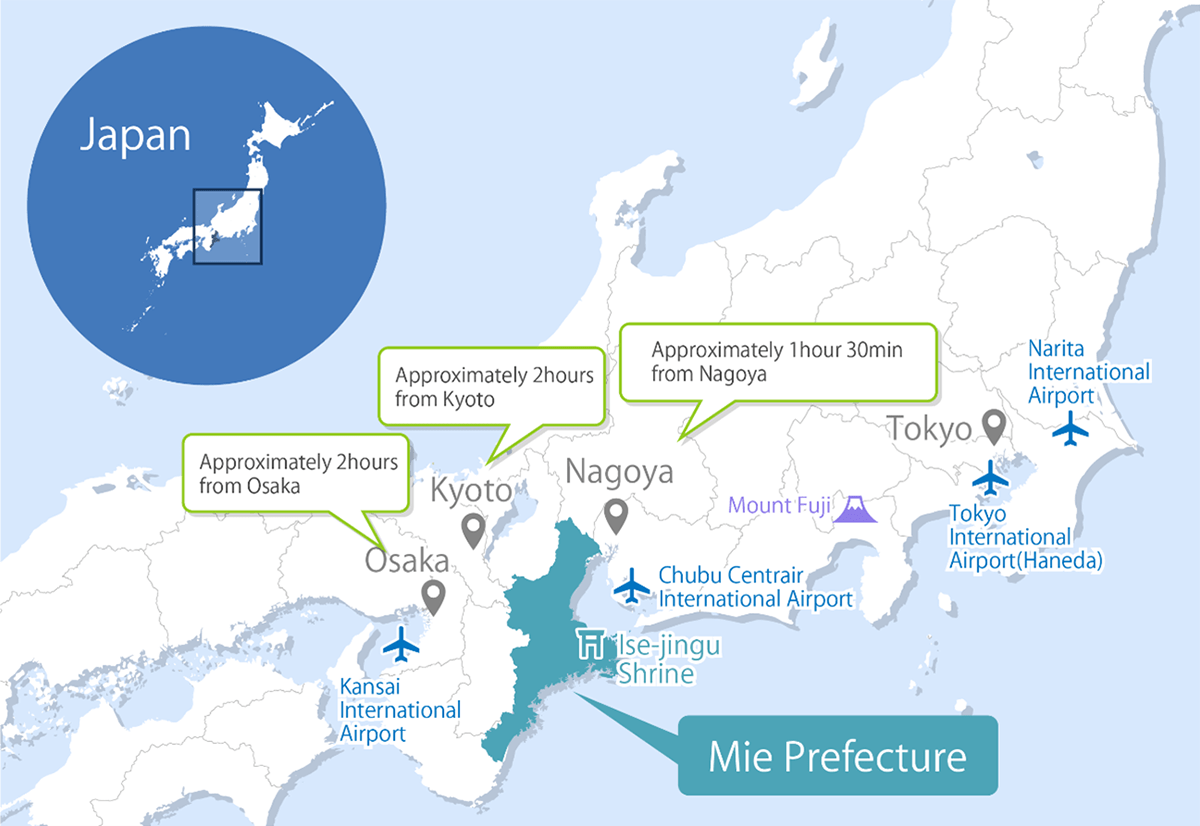

Access to Mie Prefecture

Mie Prefecture is conveniently accessible by JR (Japan Railways) and Kintetsu trains from Osaka, Kyoto, and Nagoya. Both JR and Kintetsu services provide access to Ise and Kuwana, while access to Okitsu-juku and Seki-juku is by JR only.

When traveling to Mie Prefecture by JR, the JR Pass is highly convenient. For those who wish to explore other areas mentioned in this special feature, such as the Kumano Kodo or Wakayama, the JR Tourist Pass is recommended.

Kintetsu offers direct and fast access to Mie from Osaka, Kyoto, and Nagoya without the need for transfers. The KINTETSU RAIL PASS 5 Day / 5 Day Plus provides unlimited travel on all Kintetsu lines, including Iga Railway, for five days.